Since 2017, something mysterious has been happening just 90 minutes northeast of San Francisco: A secret group has been buying up farmland — lots of it, about 60,000 acres — in rural Solano County. Many feared it could be a plot by the Chinese government to try to establish itself near Travis Air Force Base.

But as Conor Dougherty of The New York Times (who helped break the story) discovered, the truth was even stranger than the rumors.

“Like a lot of people, I was chasing him and running into the usual locked doors,” Dougherty said. “I got a tip from someone that what was behind the locked doors were the richest people in the world quietly buying up all this farmland: Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn and venture capitalist; Laurene Powell Jobs, founder of Emerson Collective and Steve Jobs’ widow; Marc Andreessen of the venture capital firm Andreesen Horowitz, truly a who’s who of Silicon Valley was involved in this.”

Another surprising thing: Just hours after Dougherty’s big scoop, this mysterious company launched a website and publicly identified itself as California Forever, an ambitious plan to build a new kind of city for up to 400,000 residents.

California forever

Jan Sramek, a 37-year-old Czech former Goldman Sachs trader turned aspiring city builder, is trying to convince the public that the project is not just an oasis for billionaires or some high-tech city of the future. His vision: turn all this farmland into a walkable city along the lines of Savannah, Philadelphia or New York’s West Village.

“Instead of taking all these good-paying jobs that are being created in Northern California and sending them to Texas or Florida, let’s create a place where we can send them to Solano County,” he said.

California Forever Urban Studio/Sitelab

So how could a city like this continue to be an accessible place for middle-class people? “Continuing to build for a long time,” Sramek said. “If we look at why places became inaccessible, it’s because they just stopped building.”

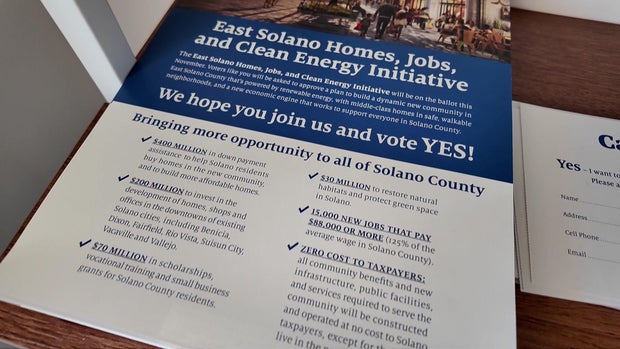

The project’s fate will finally be decided in November by Solano County voters, who will have to decide whether or not to overturn a three-decade-old law that restricts where new development can go. Sremek’s charm offensive was met with, let’s just say, a healthy amount of skepticism from many locals.

“We will have a total impasse,” said one man at a public meeting about the proposal.

Locals Al Medvitz and Jeannie McCormack are two of the last holdouts here. Most of her neighbors sold to California Forever (for far above market value), but they turned down millions to continue farming the 3,700-acre farm that has been in Jeannie’s family for more than a century. “Having developers coming was always a fear [throughout] my entire childhood,” McCormack said, “because California was changing so quickly with the development of agricultural areas.”

CBS News

Many of their neighbors who didn’t sell were sued by California Forever, which accused them of colluding to drive up land prices in the area (a charge they deny).

“Housing is important, there’s no doubt about that,” Medvitz said. “But there are appropriate ways to do this.”

California Forever is sparing no expense trying to win over county residents in what The New York Times’ Conor Dougherty says could be the most expensive political campaign in Solano County history.

CBS News

Burbank asked, “The idea that this technology money is being redirected into this kind of physical thing as an investment is kind of strange to me. Is there so much money to be made potentially?”

“Everyone thinks I’m crazy when I say this, but I just don’t think it’s primarily about money,” Dougherty said. “I think many of the people involved are extremely frustrated that the pace of change in the physical world has fallen so far behind the pace of change in the digital world.” He believes the motivation for California Forever is: “If we could redesign everything and not have to deal with all the legacy problems that cities present, it would make everything so much easier.”

California Forever still has many obstacles to overcome, some that may be impossible.

But Sramek insists that this idea of designing and building a relatively accessible and walkable city within the most expensive, car-centric state in the country is in fact possible. He says his company has the know-how, patience and (critically) resources needed to make this a reality.

“To me, success is that in 10 or 15 years, Solano County is an incredible economic success story that people all over America are looking at and saying, can we replicate that here?” Sramek said.

And does he see himself living there? “Yes, I’m moving into the first house!” he replied.

For more information:

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Ed Givnish.