Officer Dave Stiak didn’t know what to expect when he got the call that someone was hanging from a bridge railing in Lemont, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

Stiak, a deputy with the Cook County Sheriff’s Office, was on patrol with his partner in February when the calls started coming in.

“He was outside the security fence, people were calling out to him,” Stiak said. “He wasn’t responding. He was looking at the sunset. They said the guy looked like he was going to jump.”

Stiak gradually approached the man, careful not to rush him.

“I was able to reach out and put my hand on his shoulder and comfort this man… I gave the man a hug,” Stiak said. “My partner was there at the right time. We pulled him back through the fence.”

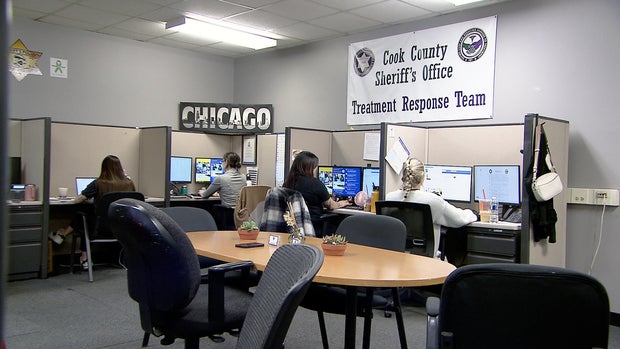

Ryan Beard/CBS News

The result was good, but it could easily have been worse. Stiak is the first to admit that police are no longer qualified to counsel people in crisis.

“They don’t train you [like] this is exactly what you do: this is the A to Z step of how to talk someone off a bridge,” Stiak said. “It’s not really a police thing.”

New ways to lessen mental health crises

Calls like the one Stiak encountered are why cities across the country are experimenting with new ways to lessen mental health crises. After the incident, Stiak gave the man a card with contact information for the sheriff’s Treatment Response Team, which can become involved during or after a mental health call.

The team is available 24/7, and while some alternative programs may send a limited number of mental health professionals onto the streets, the Cook County Sheriff’s Office places clinicians in the field as part of the response to call 911 virtually – via Zoom.

The sheriff’s office launched the Co-Responder Virtual Assistance Program, or CVAP, in late 2020. It allows deputies to connect clinicians via tablets to speak directly to people in crisis on the scene without putting counselors in danger.

In the U.S., about one in four deadly law enforcement shootings involves a person with a serious mental illness, according to a report from the Treatment Advocacy Center, an organization that pushes for reforms to treat mental health issues.

“Ultimately, in these situations where you encounter someone in crisis, the best you can hope for is to leave and for them to leave safely,” Stiak said.

The new Co-Responder Virtual Assistance Program

Elli Montgomery, executive director of the Treatment Response Team, reported the first co-responder case, which she called a success.

“A police officer who was very hesitant to work with us and was not interested in doing so, but who tried everything he could to calm an individual who was off his medication, is a boxer who suffers from bipolar disorder,” she described. “He used some substances. He was not stable.”

Courtesy of the Cook County Sheriff’s Office

Montgomery said the man repeatedly engaged in self-harm behaviors.

“He was banging his head on the floor,” she said. “He hit his head. He was just trying to smash his head against the wall.”

That’s when a sergeant present at the scene gave the man a tablet. Body camera video from officers at the scene shows the man sitting in a chair as Montgomery listened and spoke to him. He was able to discuss what happened and Montgomery finally convinced him to walk to the ambulance. The officers no longer needed to force him to get help.

Police find people in crisis

Since 2020, Cook County has received more than 1,000 suicidal calls and more than 1,300 welfare checks, according to a CBS News analysis of 911 data.

The risk of being killed when approached or stopped by authorities is 16 times greater for individuals with serious untreated mental illnesses, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center report.

This scenario repeats itself continuously across the country.

Deputies shot and killed a 15-year-old boy in Apple Valley, California, in March, who was allegedly armed with a bladed garden tool. Law enforcement previously visited the house on five separate occasionsalways taking the individual to a mental health facility.

New York City Police Officers shot and killed a 19-year-old man in front of his mother and brother in March during a mental health crisis. He allegedly ran towards the police with scissors.

These are just some of the examples that highlight the complex mental health crises that police face every day across the country.

“The police are not the experts”

In some alternative programs, dispatchers must screen 911 calls to ensure doctors don’t get into dangerous situations. Still, the circumstances described by the 911 caller can be drastically different from the scenarios officers experience when they arrive.

A CBS News data analysis of CVAP calls since 2021 showed that nearly 57% of co-responder calls were re-evaluated as a mental health issue and about 22% of calls involved substance use disorders.

Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart said CVAP gives law enforcement officers unlimited access to counselors in complex situations where police are not the experts.

“When the 911 call comes in, you’re sending an officer with police training to a home,” Dart said. “It’s fine if it’s a criminal case. Most calls everyone receives [are] based on mental health, and we’re sending the wrong person there.”

Ryan Beard/CBS News

Use of the co-responder program has grown, with 269 calls last year alone, according to an analysis of sheriff’s office data.

It showed that the most common reasons for using the co-responder program include domestic problems, suicide attempts and citizen assistance.

“If you talked to just about anyone in law enforcement, what they would tell you is that the calls they get, if there’s a domestic issue, a mental health issue, it’s not the first time they’ve been to that house, Dart said. “They go to these houses over and over again.”

“We need someone properly trained to de-escalate”

Emily Dahl, a single mother diagnosed with bipolar disorder, has had several run-ins with the police. Her family had to call police officers to her house during manic episodes.

She remembered a time when she barricaded herself in the bathroom.

“I actually ended up biting a police officer because I was in the shower,” Dahl said. “The police had been at the house for over an hour trying to take me to hospital and I was terrified.”

It wouldn’t be the last time things got physical with the police. Dahl said that in one case, when she locked herself in a room with her son, officers had to rip off the door.

“They were worried about my son’s safety,” she said.

Ryan Beard/CBS News

Officials wouldn’t be able to bring in counselors virtually in these cases, but Dahl believes it would be helpful to have one there.

“When you’re in fight or flight, you can’t reason with someone in that state,” she said. “So I think that’s where we really need help from doctors. We need someone who is properly trained to de-escalate.”

Finding qualified mental health professionals has become a challenge since the pandemic. About 49% of Americans live in an area facing mental health workforce shortages, according to the National Institute for Health Care Management.

Tim Horstman/CBS News

Sheriff: This program can work anywhere

Dart’s office said that with just 12 employees, CVAP covers 31 suburban police departments, with plans to add eight more departments this year. The program serves about 791,000 residents at a cost of $1.2 million per year, according to data provided by the Cook County Sheriff’s Office.

Their data shows that an in-person model, which would require more than 130 employees, would serve only a fraction of the population and cost about $12.9 million per year.

Tim Horstman/CBS News

“We cannot predict mental health emergencies,” said Montgomery of the Treatment Response Team. “So why would I put a salaried employee in a car who might not be able to work with anyone for eight or 10 hours?”

Montgomery said the co-responder model offers the best of both worlds, with an officer providing security and the doctor providing mental health support.

Sheriff Dart said he can’t think of a place where this program wouldn’t work.

“Success to me is being able to provide the right services to the right people immediately, not theoretically in the future, but right now,” he said.

If you or someone you know is experiencing emotional distress or suicidal crisis, you can contact the 988 Suicide and lifesaving crisis by calling or texting 988. You can also chat with the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline here.

For more information about resources and support for mental health careThe National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Helpline can be reached Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. ET, by phone at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264) or by email info@nami.org.

mae png

giga loterias

uol pro mail

pro brazilian

camisas growth

700 euro em reais