Responding to an independent review of NASA’s ambitious Mars Sample Return mission, agency officials said Monday they will seek new ideas from agency engineers, researchers and the private sector to come up with alternative mission designs to control sky-high costs and achieve precious samples. back to Earth sooner.

The independent review board concluded last September that the complex multi-spacecraft sample return mission could cost up to $11 billion to carry out – $4 billion to $5 billion more than initially expected – and not take the samples back to Earth before 2040, even extending that. outside of development.

“The NASA team that reviewed the Independent Review Board’s findings said they could extend this over time, but we won’t get the samples back until 2040,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told reporters. “It is unacceptable to wait so long. It is in the 2040s that we will land astronauts on Mars.”

NASA

He said the estimated price tag, which could reach $11 billion depending on the options adopted, was also “unacceptable.” The original goal of a decennial National Science Foundation survey that recommended a sample return mission was just under $6 billion.

“The bottom line is that the current budget environment does not allow us to pursue an $11 billion architecture, and 2040 is too long,” Nelson said. “So what to do?

“I’ve asked our people to solicit information from industry, from JPL, from all NASA centers (and) to report this fall on an alternative plan that would bring (the samples) back faster and cheaper, and try to stay within the limits that the decennial survey said we should.”

After the conference call concluded, SpaceX founder Elon Musk said on X that his company’s Starship rocket, which NASA’s Artemis astronauts will use to reach the Moon’s surface in the coming years, “has the potential to return a large tonnage from Mars within (about) 5 years.”

No immediate comment on this NASA idea.

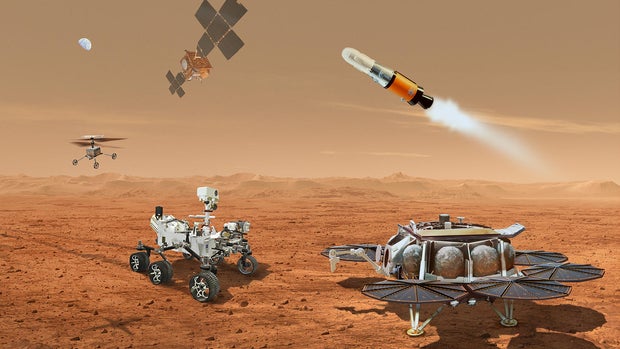

As originally envisioned, the Mars Sample Return, or MSR, mission is the most complex planetary robotic science mission ever attempted, requiring a new NASA lander to bring a rocket to the surface capable of launching soil and rock samples collected by another rover. already in operation. the red planet.

Once in Mars orbit, the sample container would be collected by a European Space Agency spacecraft and returned to Earth for detailed laboratory analysis to determine whether any signs of past microbial activity could be present in ancient riverbed deposits.

NASA

NASA originally expected to launch the MSR mission, with a projected life-cycle cost of nearly $6 billion, in 2028. But in September 2023, the independent review board concluded that the project was not viable given current budget projections. , unrealistic timelines, and a management structure that was not up to the task of preparing the spacecraft for launch on time.

The review panel concluded that the project almost certainly could not get off the ground before 2030 and could cost between $8.4 billion and $10.9 billion, depending on the mission’s final architecture.

“MSR is a deep space exploration priority for NASA, in collaboration with ESA,” the review team concluded. “However, MSR was established with unrealistic budget and calendar expectations from the beginning. MSR was also organized under an unwieldy structure.

“As a result, there is currently no credible and congruent technical basis, nor a properly defined timetable, cost and technical basis that can be achieved with the likely available funding.”

The team said that “technical issues, risks and performance to date indicate a near-zero probability of… meeting the 2027/2028 launch readiness dates (LRDs). There are potential LRDs in 2030, provided there is adequate funding and resolution of problems.”

To launch in 2030, NASA’s sample retrieval module and ESA’s Earth Return Orbiter will likely require between $8 billion and $9.6 billion, “with funding in excess of $1 (billion) per year per year. be necessary for three or more years from 2025”.

NASA

Alternative mission scenarios and the launch of ESA’s sample retrieval rover and orbiter on different timetables between 2030 and 2035 could “yield an MSR program that is potentially able to fit within likely annual funding constraints.” But the costs could reach nearly $11 billion, more than NASA spent to build the James Webb Space Telescope.

Nelson said the main reason for the cost increase was a billion-dollar hit to NASA’s science budget, which was part of a congressional deal to secure funding for the debt ceiling. NASA received $310 million for the sample return mission in the agency’s fiscal 2024 budget and plans to ask for just $200 million in the fiscal 2025 budget request while mission options are explored.

However the mission unfolds, the samples will be waiting. Since landing in Jezero Crater in February 2021, NASA Rover Perseverance he was collecting soil and rock samples, storing them on board in sealed tubes or dropping them to the surface in known locations for eventual recovery. The samples were collected near an ancient delta where water once flowed into the crater, possibly depositing indicators of past biological activity.

Although Perseverance is equipped with sophisticated instruments and laboratory equipment, it was designed primarily to assess habitability, not to look for signs of past microbial life. For this type of in-depth research, samples must be brought back to Earth.

Under the initial MSR plan, a NASA recovery rover would land near the Perseverance samples, collect them with a robotic arm or small helicopters, and place them inside a sample container atop a solid-fuel rocket. known as the Mars Ascension Vehicle. The MAV would then lift off and launch the sample container into Mars orbit.

At that point, ESA’s recovery spacecraft would rendezvous with the sample spacecraft, capture it, and return to Earth. The sample container would then be released for a parachute descent to a landing site in the US. From there, it would be transported to a laboratory at the Johnson Space Center to begin detailed analysis.