In 1943, Vincent Speranza, the son of Italian immigrants, enlisted when he turned 18. “I decided to be a paratrooper when I discovered it was probably the quickest way to get into battle,” he said. “We were innocent children who weren’t ready for what was coming, let me tell you.”

He fought in the Battle of the Bulge – Hitler’s last attempt to avoid defeat in the final months of the war in Europe.

“Twelve thousand Americans in that city resisted 56,000 German soldiers,” Speranza said.

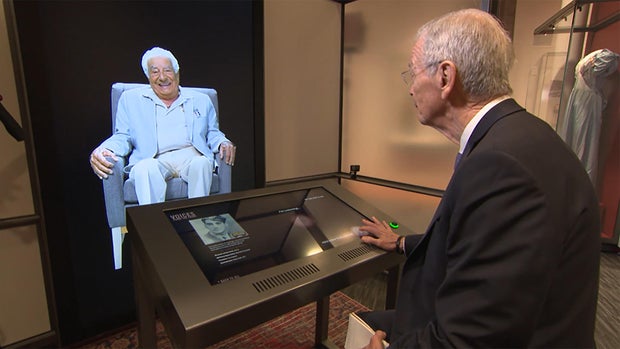

Hope died last year at age 98. But visitors to the National World War II Museum in New Orleans can still “talk” to him, thanks to voice recognition software and artificial intelligence. By asking questions, answers from interviews conducted with Speranza and other veterans can be reproduced, preserving not only the stories of the Second World War, but also the people who lived through them.

Q: “Did you have any problems?”

Speranza: “I was trying to take a drink from my canteen… and it slipped out of my hands, and as I bent down to pick up the canteen, a bullet went through my helmet. If I had been standing up, it would have gone right through the middle of my chest.”

CBS News

“Unfortunately we are reaching a time when there are fewer and fewer World War II veterans to talk to,” said museum vice president Peter Crean.

Eighteen veterans of the war effort each sat down for two days of interviews in a specially configured Hollywood studio. “We asked them about a thousand questions,” Crean said.

Bomber pilot John Luckadoo was one of the participants. He said that recording the interview was “an extremely intriguing concept – the idea that my great-great-grandchildren could talk to me and ask me anything that came to mind, and it would automatically scroll to my answer.”

And not just Luckadoo’s great-great-grandchildren – everyone’s great-great-grandchildren will be able to do it.

Luckadoo was 20 years old when he flew bombing missions over Germany. “They were as dangerous as you can imagine because we were facing a formidable German Air Force that had been fighting for four years,” he said.

Luckadoo said that if you survived 25 missions, you would be eligible to return to the United States. The chances of surviving 25 missions were less than one in four.

Now 102 years old, Luckadoo saw for the first time how he will be remembered. He asked his avatar: “What was your worst mission?”

The recorded Luckadoo responded: “When we started the bombardment, we had a formation of 18 ships. We lost 12 of the 18 ships, instantly.”

CBS News

“It’s kind of weird talking to yourself!” he said about approaching his recording.

“So this is the me that generations will know,” Martin said. “Are you okay with this?”

“Well, it will be interesting to see how the generations react to this,” Luckadoo replied. “It’s not very important how I react to it.”

React not only to his war stories, but also to what happened when he returned home. Luckadoo recorded his experience: “They rationed us to a fifth of whiskey a day. I soon realized that wasn’t enough. I was quickly becoming an alcoholic.”

Martin said: “Young generations will discover this about you too.”

“Well, I wanted to convey the fact that this is the kind of state you could be in if you lived through what we experienced back then – that war does this, can do this to you,” Luckadoo responded.

History archive

“Fear in war is something that is always present.”

Anyone can ask Woody Williams about seeing the American flag raised on Iwo Jima, Mount Suribachi. Until his passing in 2022, Williams was the last living Medal of Honor recipient from the war. “I received the Medal of Honor for eliminating the enemy in seven boxes of pills on Iwo Jima,” he said in his interview.

The war was not just won on the battlefield. Grace Brown was a “Rosie the Riveter” who made parts for bombers. “I think I was a good train driver because I loved math,” she said in her remembrance.

Crean said, “The war was fought and won by the average guy who lived on the street or the woman who was a nurse or worked in the factory.”

Corbett Summers, whose father served in World War II, was one of the first members of the public to see the new exhibit. He called it oppressive. “Everyone should have the opportunity to see this generation,” he said. “I could be there all day talking to each of them and hearing their stories and what they went through.”

You can read all the great stories of war and never find a better answer to what combat is really like than that of the late Vincent Speranza: “In your spinning mind, the most important thought you had was, ‘Will I be able to stand up and then have my friends tell me, yes, you are a combat soldier’?”

More than 600,000 visitors a year can hear firsthand from veterans like Tuskegee Airman George Hardy about a time when everything was at stake. “I was assigned to the 99th Fighter Squadron, part of the 333rd Second Fighter Group in Italy,” Hardy said.

CBS News

Luckadoo spoke about the importance of preserving eyewitness accounts: “Lives were spent protecting our freedom and our values and what we considered our ideals and democracy.”

Martin asked, “Do you think people today have a good understanding of World War II?”

“Certainly not,” replied Luckadoo. “The biggest thing they don’t understand is how the civilian population – those who didn’t wear uniforms, and particularly women – came together in support of the war effort. We were united like we’ve never been before and, unfortunately, we probably never will be again.”

For more information:

Story produced by Mary Walsh and Eleanor Watson. Editor: José Frandino.

See too:

mae png

giga loterias

uol pro mail

pro brazilian

camisas growth

700 euro em reais